Understanding Ammunition

Ammunition is the projectile with its fuse, propelling charge, or primer that is fired from guns. Ammunition comes in a bewildering proliferation of variations for many specific purposes. We have tried to provide some information to help you wind your way through the maze.

Remember, too, that best cartridge in the world does you absolutely no good if you miss your shot. Practice, practice, practice!

Ammunition Basics

Anatomy

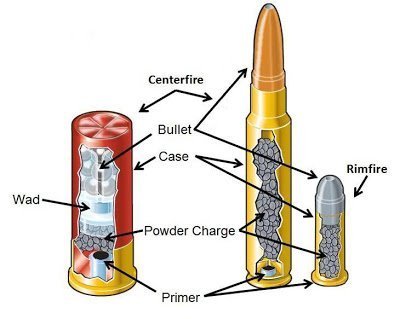

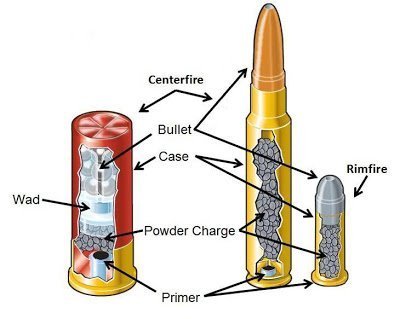

The basic components of ammunition are the case, primer, propellant, and projectile.

- case

-

The container that holds all the other ammunition components together. It’s usually made of brass, steel, or copper.

- primer

-

An explosive chemical compound that ignites the gunpowder when struck by a firing pin. Primer may be placed either in the rim of the case (rimfire) or in the center of the base of the case (centerfire).

- propellant

-

A chemical mixture, e.g. gunpowder, that burns rapidly and converts to an expanding gas when ignited.

- projectile

-

The object expelled from the barrel. A bullet is a projectile, usually containing lead, fired through a handgun barrel. A shotgun shell usually has multiple projectiles, called shot.

A shotgun shell also has a wad. This is a paper or plastic barrier that holds the propellant in the bottom of the shell and helps to push the projectiles out.

Caliber

Caliber is the nominal diameter of a projectile of a rifled firearm or the diameter between lands in a rifled barrel. In the United States, caliber is usually expressed in hundredths of an inch; in Great Britain in thousandths; in Europe and elsewhere in millimeters.

Any firearm is designed for a specific caliber, which will be on the firearm somewhere. You must have the correct caliber for your firearm. Some common calibers used for defense are: 9mm, .380, .38 special, .357, .40, .45, and 12 gauge.

The best caliber for you is the one you feel the most comfortable shooting. Find a reliable firearm that fits you, spend time practicing, and use high-quality self defense ammo (of course, for practicing you can use target rounds). You should understand how it will behave when fired. For example, how far will it go? Should you be worried about your neighbor, even if you live in the East Mountains and the nearest neighbor is a quarter mile away? What will it go through?

The term used for shotgun shells is gauge. In a confusing system that dates back to cannons, shotgun gauges are measured in the weight of a solid sphere of lead that will take up the entire bore. So a 12 gauge barrel fits a lead ball that is 1/12 of a pound and a 20 gauge fits one that is 1/20 of a pound. The larger the number, the smaller the diameter of the shotgun barrel. As with caliber, you can only shoot the correct gauge in your shotgun.

Grain

The term grain refers to the mass/weight (physicists will tell you they are not the same, but for our purposes on the surface of this planet, they are) of the projectile. A grain is a very small unit of measurement; 1 grain equals 64.7989 mg, 7,000 grains equals 1 pound, and 437.5 grains equals 1 ounce.

Grain is also used as a measurement for the gunpowder. On a box of ammunition, though, the grains virtually always refers to the weight of the projectile.

The weight of the bullet affects both how it flies and how it performs when it hits. A lighter bullet has a flatter trajectory and greater velocity, while a heavier one travels more slowly but hits with greater momentum.

Some other terms and acronyms used with ammunition are defined below:

- ACP

-

Automatic Colt Pistol. A semi-rimmed straight-walled centerfire pistol cartridge introduced by John Browning in 1905. It was designed to have similar ballistics to a .22LR but fired from a short barrel.

- FMJ

-

Full Metal Jacket. The projectile is completely encased with a harder metal coating, allowing for higher muzzle velocities without leaving lead in the barrel. These do not expand upon impact, causing less damage to soft targets such as living creatures. They do penetrate hard targets more efficiently, meaning they will go through barriers such as walls more easily.

- FPS

-

Feet Per Second. Refers to the fastest velocity of the bullet, usually near the muzzle. Lighter bullets usually move at higher velocities.

- JHP

-

Jacketed Hollow Point. Hollow points are designed to expand once they are in the target, maximizing tissue damage and blood loss. They also allow the bullet to remain within the target, thereby ensuring that all the kinetic energy is applied to the target. Jacketed or plated hollow points have a coating of harder metal to increase bullet strength and help prevent lead stripped from the bullet from remaining in the barrel.

- JSP

-

Jacketed Soft Point. This is a bullet with an exposed lead tip.

- magnum

-

A magnum cartridge is generally a longer case with more propellant than the standard for the projectile size.

- +P

-

overPressurized. Ammunition with a higher pressure than standard for its caliber, resulting in faster muzzle velocity and greater penetration. Some handguns deal well with the stress of +P ammunition, others . . . don't.

- SWC

-

Semi-WadCutter. A bullet with a blunted tip. These will “punch” a big hole in your target.

Pew Pew Tactical has a fairly thorough description of bullet sizes, calibers, and types. The Springfield Armory has an interesting article which also goes through more specifications than we have covered here. Concealed Nation has a nice comparison of various types of ammunition.

For shotguns, The Well Armed Woman has a useful article about shotgun ammunition. Gizmodo also has an article on shotgun shells.

There are also many other articles available to help you learn more.

Return to top

Does Caliber Matter?

Does caliber really matter when it comes to a defensive handgun? A form of this argument has existed since the beginning—how big a rock do you really need in a slingshot? In our culture, caliber affects the perception of “manliness” or gunslinging prowess. The lowly .22LR is a “mouse” gun, while the .357 is a cannon. Can we find a definitive answer? Let's explore the topic a little.

The Research

Much research exists, and volumes of data have been collected, but it can all be sliced a thousand different ways. In his 2011 article An Alternate Look at Handgun Stopping Power, Greg Ellifritz at the Buckeye Firearms Association analyzed and published data that he collected over a 10 year period. There were some surprising results. The use of .22s in a gunfight have a higher than average percent of fatalities, and required fewer than average number of rounds to incapacitate an opponent except for shotguns.

The one negative statistic related to .22s concerned shootings where the opponent was not incapacitated by any number of rounds. This caliber had the highest percentage of all calibers at 40%, a statistic that should certainly give you pause if you are considering a .22LR as a carry firearm.

Ellifritz admits the statistic can’t stand on its own. The failure to incapacitate could be related to the fact that inexperienced and less trained people tend to gravitate toward a .22LR as a relatively safe gun for them. Shots wide of center mass by inexperienced or untrained shooters could impact this particular statistic. By the same token, the high number of fatalities could be the result of experienced shooters being able to accurately deliver effective rounds to their opponents' vital areas.

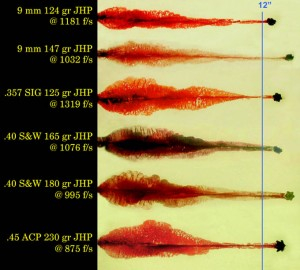

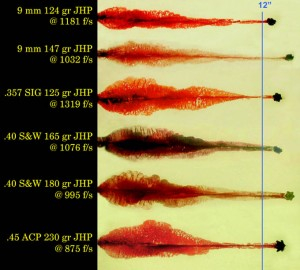

David Morris, who writes the online Tactical Preparedness Newsletter, looked at the data from a wound effectiveness perspective. The wound effectiveness of subsonic projectiles (bullets, in this case) depends on two factors: 1) the volume of tissue crushed or swept out by the projectile, and 2) the potential for rapid blood loss. The first is affected by the swath of the bullet on impact, which is related to the type of bullet and the size. The second is determined by the penetration, especially if the bullet leaves two areas for bleed out (an entry and an exit wound).

Morris used various rounds of JHP (jacketed hollow point) at two different grains, or weights, to shoot into gel. His results are shown to the left. They all had roughly the same penetration, and might pass through a body depending on what anatomical structures the bullet hits on its way through the body.

It appears the 9mm rounds affected a lesser area of the gel, but recent data from the FBI suggests it takes an average of 3 rounds of 9mm, .40, or .45 to stop a threat, so the larger size of the bullet swath doesn’t seem to be increasing stopping power that much.

It appears the 9mm rounds affected a lesser area of the gel, but recent data from the FBI suggests it takes an average of 3 rounds of 9mm, .40, or .45 to stop a threat, so the larger size of the bullet swath doesn’t seem to be increasing stopping power that much.

To illustrate that point, Morris shows this photo of a bullet smashed to .56 caliber, and asks what caliber of bullet this is? It's a 9mm, if you can believe it.

Anecdotal Evidence

Beyond the data, there are trends in the military and law enforcement to lower calibers. Some organizations are going back to 9mm from .40 or .45 calibers. Their personnel can qualify more easily with the lower caliber—they are more accurate—and they tend to weigh less, which is important when someone carries it for 8-12 hours a day.

Some police say just pointing a gun at an opponent was pretty effective at stopping them. No one asked, “Hey, how big is that gun you got?” People don’t want to get shot, no matter what caliber the gun is.

The data indicate that some opponents stopped after being shot once, even though they were not incapacitated. This is referred to as a “psychological” stop. The opponent gives up the fight mentally, regardless of the caliber he was shot with. A lot of anecdotal evidence supports the view that caliber isn’t always that important.

Opinion

David Morris says when you are as good as you can get as a shooter, you might consider a higher caliber. Until then, the best caliber for a defensive pistol for you is the one that allows you to put fast, accurate, threat stopping shots in as many targets as are posing a violent threat to you. The USCCA (U.S. Concealed Carry Association) recommends following a guideline proposed by Gila Hayes in her book, Effective Defense. Her standard is to put 5 shots in a 5 inch diameter circle at 5 yards in 5 seconds to determine if a particular gun is for you. This is a good balance between shooting accurately and shooting quickly.

There is no definitive answer to the question, “Does caliber matter?” You have to be comfortable and confident with the handgun you choose. Maybe shooters should spend more time honing basic skills as shooters and less time worrying about what caliber is most impressive.

Return to top

Understanding 9mm Ammunition

Jodi & Michelle

How hard can it be to buy 9mm ammunition? Well, the more you know, the more complicated it gets. And it pays to know more—ammunition is not cheap and, more importantly, it’s not returnable!

Let’s talk about some of the types of 9mm you see when you shop for ammo.

- 9mm Luger

-

This is a typical designation for the modern 9mm cartridge. The 9mm was developed in 1902 by Georg Luger to improve on the shortcomings of the .380 caliber round that was then in wide use in the military, and designed for the Luger pistol.

- Parabellum

-

Luger named the cartridge the 9mm Parabellum—Latin for “prepare for war”, from the phrase, Si vis pacem, para bellum, meaning “If you want peace, prepare for war”. Popularly, it was called the 9mm Luger, and SAAMI, the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute founded in 1926, adopted Luger as the official designation for the cartridge. Parabellum is a term you won’t see often, but you hear people referring to it.

- 9x19

-

You can also see this on a 9mm ammo box. This happens to be the diameter (9mm) of the projectile and the length (19mm) of the case of the cartridge.

- 9x18 Makarov

-

This round was made for the Russian Makarov pistol. As you can probably guess after reading about the 9x19, this cartridge is 1mm shorter than the 9x19. In addition, the bullet is 0.01 inch larger than the standard 9mm. When used in any other pistol, the case will get stuck because of this slight different in bullet diameter—just ask Jodi Newton and Bob at Mags!

- 9mm NATO

-

The dimensions of this cartridge are the same as the 9mm Luger/Parabellum/9x19, but the powder load is not. This means this cartridge develops a significantly higher pressure when fired. Most high quality modern pistols can handle this load—Springfield, Ruger, Glock, S&W—but be careful with bargain basement manufacturers. Please refer to your pistol’s manual or contact the manufacturer. Even with quality guns, a steady diet of these cartridges will increase the wear and tear on your gun.

- 9mm +P

-

“Plus P” in any caliber means that there is more pressure developed when fired, like the 9mm NATO cartridge. This is popular for self-defense cartridges, but again, check your manual to see if this ammo is right for your pistol!

Many people have different ideas about all these ammo types and whether they are interchangeable or not. This information was researched by Jodi and Michelle, and they are confident it is good info! Your takeaway from this is: if the box says anything other than 9mm Luger, Parabellum, or 9x19, proceed with caution. If you are uncertain, take your pistol manual to the gun shop with you and ask a salesperson to verify that what you have selected is compatible with your pistol.

Return to top

It appears the 9mm rounds affected a lesser area of the gel, but recent data from the FBI suggests it takes an average of 3 rounds of 9mm, .40, or .45 to stop a threat, so the larger size of the bullet swath doesn’t seem to be increasing stopping power that much.

It appears the 9mm rounds affected a lesser area of the gel, but recent data from the FBI suggests it takes an average of 3 rounds of 9mm, .40, or .45 to stop a threat, so the larger size of the bullet swath doesn’t seem to be increasing stopping power that much.